Plurality philosophy in an incredibly oversized nutshell

2024 Aug 21

See all posts

Plurality philosophy in an incredibly oversized nutshell

Special thanks to Glen Weyl and Audrey Tang for discussion and

Karl Floersch for review.

One of the interesting tensions in the crypto space, which has become

a sort of digital home for my

geographically nomadic self over the last decade, is its

relationship to the topic of governance. The crypto space hails

from the cypherpunk movement, which values independence from

external constraints often imposed by ruthless and power-hungry

politicians and corporations, and has for a long time built technologies

like torrent networks and encrypted messaging to achieve these ends.

With newer ideas like blockchains, cryptocurrencies and DAOs, however,

there is an important shift: these newer constructions are long-lived,

and constantly evolving, and so they have an inherent need to

build their own governance, and not just circumvent the governance of

unwanted outsiders. The ongoing survival of these structures

depends crucially on mathematical research, open source software, and

other large-scale public goods. This requires a shift in mentality: the

ideology that maintains the crypto space needs to transcend the ideology

that created it.

These kinds of complex interplays between coordination and freedom,

especially in the context of newer technologies, are everywhere in our

modern society, going far beyond blockchains and cryptocurrency. Earlier

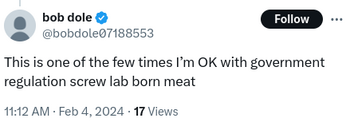

this year, Florida governor Ron DeSantis signed a

bill that would ban synthetic (aka "lab-grown") meat from the state,

arguing that "global elites want to control our behavior and push a diet

of petri dish meat and bugs on Americans", and that we need to

"prioritize our farmers and ranchers over ... the World Economic Forum".

As you might expect, the Libertarian Party New Hampshire account

publicly criticized the "authoritarian

socialist" nature of the legislation. But as it turned out, many

other self-described libertarians did not share the same opinion:

To me, LPNH's criticism of DeSantis's ban makes total sense: banning

people from eating a new and potentially far more ethical and

sustainable form of meat, on the basis of little more than a disgust

reflex, is the exact opposite of valuing freedom. And yet, it's clear

that many others do not feel the same way. When I scoured the internet

for cogent arguments why, the most compelling I could find is this argument

from Roko Mijic: in short, once something like this is allowed, it

becomes mainstream, society reorganizes around it, and the lives of

those who do not want to follow along inevitably become harder and

harder. It happened with digital cash, to the point where even the

Swedish central bank is worried about cash payments accessibility,

so why wouldn't it happen in other sectors of technology as well?

About two weeks after the DeSantis signed the bill banning lab-grown

meat, Google announced that it was rolling out

a feature into Android that would analyze the contents of calls in

real time, and would automatically give the user a warning if it thinks

the user might be getting scammed. Financial scams are a large and

growing problem, especially in regions like Southeast Asia, and they are

becoming increasingly sophisticated more rapidly than many people can

adapt. AI is accelerating

this trend. Here, we see Google, creating a solution to help warn

users about scams, and what's more, the solution is entirely

client-side: there's no personal data being shipped off to any

corporate or governmental Big Brother. This seems amazing; it's

exactly the kind of tech that I advocated for in my

post introducing "d/acc". However, not all freedom-minded people

were happy, and at least one of the detractors was very difficult to

dismiss as "just a Twitter troll": it was Meredith Whittaker, president

of the Signal Foundation.

All three of these tensions are examples of things that have made a

deep philosophical question repeatedly pop into my mind: what is

the thing that people like myself, who think of ourselves as principled

defenders of freedom, should actually be defending? What is the

updated version of Scott Alexander's notion of liberalism

as a peace treaty that makes sense in the twenty first century?

Clearly, the facts have changed. Public goods are much more important

than before, at larger scales than before. The internet has made

communication abundant, rather than scarce. As Henry Farrell analyzed in

his

book on weaponized interdependence, modern information technology

doesn't just empower the recipient: it also enables ongoing power

projection by the creator. Existing attempts to deal with these

questions are often haphazard, trying to treat them as exceptions that

require principles to be tempered by pragmatic compromise. But what if

there was a principled way of looking at the world, which values freedom

and democracy, that can incorporate these challenges, and deal with them

as a norm rather than an exception?

Table of contents

Plurality, the book

The above is not how Glen Weyl and Audrey Tang introduce

their new book, Plurality: the

future of collaborative technology and democracy. The narrative that

animates Glen is a somewhat different one, focusing on the increasingly

antagonistic relationship between many Silicon Valley tech industry

figures and the political center-left, and seeking to find a more

collaborative way forward:

Glen Weyl, introducing the Plurality book in a presentation in

Taipei

But it felt more true to the spirit of the book for me to give an

introduction that gestures at a related set of problems from my own

angle. After all, it is an explicit goal of Plurality to try to be

compelling to a pretty wide group of people with a wide set of concerns,

that draw from all different parts of the traditional political

spectrum. I've long been concerned about what has felt to me like a

growing decline of support for not just democracy but even freedom,

which seems to have accelerated since around 2016.

I've also had a front-row seat dealing with questions of governance

from the governance builder's side, from my role within the Ethereum

ecosystem. At the start of my Ethereum journey, I was originally

animated by the dream of creating a governance mechanism that was

provably mathematically optimal, much like we have provably optimal consensus

algorithms. Five years later, my intellectual exploration ended up

with me figuring out the theoretical

arguments why such

a thing is mathematically

impossible.

Glen's intellectual evolution was in many ways different from mine,

but in many ways similar. His previous book Radical

Markets featured ideas inspired by classical liberal economics, as

well as more recent mathematical discoveries in the field, to try to

create better versions of property rights and democracy that solve the

largest problems with both mechanisms. Just like me, he has always found

ideas of freedom and ideas of democracy both compelling, and has tried

to find the ideal combination of both, that treats them not as opposite

goals to be balanced, but as opposite sides of the same coin that need

to be integrated. More recently, just like what happened with me, the

mathematical part of his social thinking has also moved in the direction

of trying to treat not just individuals, but also

connections between individuals, as a first-class object that

any new social design needs to take into account and build

around, rather than treating it as a bug that needs to be

squashed.

It is in the spirit of these ideas, as well as in the spirit of an

emerging transition from theory to practice, that the Plurality book is

written.

How would I define

Plurality in one sentence?

In his 2022 essay "Why

I Am A Pluralist", Glen Weyl defines pluralism most succinctly as

follows:

I understand pluralism to be a social philosophy that recognizes and

fosters the flourishing of and cooperation between a diversity of

sociocultural groups/systems.

If I had to expand on that a little bit, and define Plurality the

book in four bullet points, I would say the following:

- Glen's megapolitics: the idea that the world today

is stuck in a narrow

corridor between conflict and centralization, and we need a new and

upgraded form of highly performant digital democracy as an alternative

to both.

- Plurality the vibe: the general theme that (i) we

should understand the world through a patchwork combination of models,

and not try to stretch any single model to beyond its natural

applicability, and (ii) we should take connections between

individuals really seriously, and work to expand and strengthen

healthy connections.

- Plurality-inspired mechanism design: there is a set

of principled mathematical techniques by which you can design social,

political and economic mechanisms that treat not just

individuals, but also connections between individuals

as a first-class object. Doing this can create newer forms of markets

and democracy that solve common problems in markets and democracy today,

particularly around bridging tribal divides and polarization.

- Audrey's practical experience in Taiwan: Audrey has

already incorporated a lot of Plurality-aligned ideas while serving as

Digital Minister in Taiwan, and this is a starting point that can be

learned from and built upon.

The book also includes contributions from many authors other than

Glen and Audrey, and if you reach the chapters closely you will notice

the different emphases. However, you will also find many common

threads.

What are the

megapolitics of Plurality?

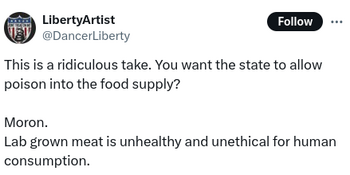

In Balaji Srinivasan's magnum opus The

Network State, Balaji described his vision of the current world as

being split between three poles: center-left Anglosphere elites

exemplified by the New York Times (NYT), the Chinese Communist Party

(CCP), and ultra-individualistic right-leaning people as exemplified by

Bitcoin (BTC). Glen, both in the Plurality book and elsewhere,

has given his own characterization of the "political ideologies of the

21st century", that looks as follows:

The names of the three are taken from Civilization 6,

and in the Plurality book Glen simplifies the names to

Technocracy, Libertarianism and

Plurality. He describes the three roughly as

follows:

- (Synthetic) Technocracy: some mechanism run by a

combination of AI and a small human elite creates lots of amazing stuff,

and makes sure that everyone gets the share they need to live a good

life (eg. via UBI). Political input from non-elites is considered

unimportant. Examples of this ideology include the Chinese Community

Party, the World Economic Forum ("you will own nothing and you will be

happy"), Sam

Altman and friends' UBI advocacy, and from my recent travels, I

would perhaps add the Dubai

Museum of the Future.

- (Corporate) Libertarianism: maximize security of

property rights and freedom of contract, and expect that most important

projects are started by some kind of "great founder" entrepreneur.

Individuals are protected from abuse almost entirely through the right

to "exit" any system that becomes too inefficient or exploitative.

Examples of this ideology include books like The

Sovereign Individual, free city movements like Prospera,

as well as network states.

- Digital democracy / Plurality: use internet-enabled

technology to create much more high-bandwidth democratic mechanisms that

can aggregate preferences from a very wide group of people, and use

these mechanisms to create a much more powerful and effective

"third-sector" or "civil society" that can make much better decisions.

Examples that Glen cites include both fiction, most notably Star Trek

and anything by Ursula le

Guin, and real-life proto-examples, most notably e-government in

Estonia and Taiwan.

Glen sees Plurality as being uniquely able to simultaneously avoid

three failure modes: coordination failure leading to

conflict (which he sees Libertarianism as risking),

centralization and authoritarianism (which he sees

Technocracy as risking), and stagnation (which he sees

"old-world democracy" as risking, causing it to lose competitiveness

against Libertarianism and Technocracy). Glen sees Plurality as an

under-explored alternative which it is his project to flesh out as an

idea, and Audrey's project to bring to life, first in Taiwan then

elsewhere.

If I had to summarize the difference between Balaji's program and

Glen and Audrey's program, I would do so as follows. Balaji's vision

centers around creating new alternative institutions and new communities

around those new institutions, and creating safe spaces to give them a

chance to grow. Glen and Audrey's approach, on the other hand, is best

exemplified by her "fork-and-merge"

strategy in e-government in Taiwan:

So, you visit a regular government website, you change your O to a

zero, and this domain hack ensures that you're looking at a shadow

government versions of the same website, except it's on GitHub, except

it's powered by open data, except there's real interactions going on and

you can actually have a conversation about any budget item around this

visualization with your fellow civic hackers.

And many of those projects in Gov Zero became so popular that the

administration, the ministries finally merged back their code so that if

you go to the official government website, it looks exactly the same as

the civic hacker version.

There is still some choice and exit in Audrey's vision, but

there is a much tighter feedback loop by which the improvements created

by micro-exits get merged back into "mainline" societal

infrastructure. Balaji would ask: how do we let the synthetic

meat people have their synthetic meat city, and the traditional meat

people have their traditional city? Glen and Audrey might rather ask:

how do we structure the top levels of society to guarantee people's

freedom to do either one, while still retaining the benefits of being

part of the same society and cooperating on every other axis?

What is the

Plurality model of "the world as it is"?

The Plurality view on how to improve the world starts with a

view on how to describe the world as it is. This is a key part

of Glen's evolution, as the Glen of ten years ago had a much more

economics-inspired perspective toward these issues. For this reason,

it's instructive to compare and contrast the Plurality worldview with

that of traditional economics.

Traditional economics focuses heavily on a small number of economic

models that make particular assumptions about how agents operate, and

treats deviations from these models as bugs whose consequences are not

too serious in practice. As given in textbooks, these assumptions

include:

- Competition: the common

case for the efficiency of markets relies on the assumption that no

single market participant is large enough to significantly move market

prices with their actions - instead, the prices they set only determine

whether or not anyone buys their product.

- Perfect information: people in a market are fully

informed about what products they are purchasing

- Perfect rationality: people in a market have

consistent goals and are acting toward achieving those goals (it's

allowed for these goals to be altruistic)

- No externalities: production and use of the things

being traded in a marketplace only affects the producer and user, and

not third parties that you have no connection with

In my own recent writing, I generally put a stronger emphasis on an

assumption that is related to competition, but is much stronger:

independent choice. Lots of mechanisms proposed by

economists work perfectly if you assume that people are acting

independently to pursue their own independent objectives, but break down

quickly once participants are coordinating their actions though some

mechanism outside of the rules that you set up. Second price auctions

are a great example: they are provably perfectly efficient if the above

conditions are met and the participants are independent, but break

heavily if the top bidders can collude. Quadratic

funding, invented by myself, Glen Weyl and Zoe Hitzig, is similar:

it's a provably ideal mechanism for funding public goods if participants

are independent, but if even two participants collude, they can extract

an unbounded amount of money from the mechanism. My own work in pairwise-bounded

quadratic funding tries to plug this hole.

But the usefulness of economics breaks down further once you start to

analyze incredibly important parts of society that don't look like like

trading platforms. Take, for instance, conversations. What are the

motivations of speakers and listeners in a conversation? As Hanson and

Simler point out in The Elephant In The

Brain, if we try to model conversations as information

exchange, then we would expect to see people guarding information

closely and trying to play tit-for-tat games, saying things only in

exchange for other people saying things in return. In reality, however,

people are generally eager to share information, and criticism of

people's conversational behavior often focuses on many people's tendency

to speak too much and listen too little. In public

conversations such as social media, a major topic of analysis is what

kinds of statements, claims or memes go viral - a term that

directly admits that the most natural scientific field to draw analogies

from is not economics, but biology.

So what is Glen and Audrey's alternative? A big part of it is

simply recognizing that there is simply no single model or scientific

approach that can explain the world perfectly, and we should

use a combination of different models instead, recognizing the limits of

the applicability of each one. In a key

section, they write:

Nineteenth century mathematics saw the rise of formalism: being

precise and rigorous about the definitions and properties of

mathematical structures that we are using, so as to avoid

inconsistencies and mistakes. At the beginning of the 20th century,

there was a hope that mathematics could be "solved", perhaps even giving

a precise algorithm for determining the truth or falsity of any

mathematical claim.[6] 20th century mathematics, on the other hand, was

characterized by an explosion of complexity and uncertainty.

- Gödel's Theorem: A number of mathematical results

from the early 20th century, most notably Gödel's theorem, showed that

there are fundamental and irreducible ways in which key parts of

mathematics cannot be fully solved.

- Computational complexity: Even when reductionism is

feasible in principle/theory, the computation required to predict

higher-level phenomena based on their components (its computational

complexity) is so large that performing it is unlikely to be practically

relevant.

- Sensitivity, chaos, and irreducible uncertainty:

Many even relatively simple systems have been shown to exhibit "chaotic"

behavior. A system is chaotic if a tiny change in the initial conditions

translates into radical shifts in its eventual behavior after an

extended time has elapsed

- Fractals: Many mathematical structures have been

shown to have similar patterns at very different scales. A good example

of this is the Mandelbrot set.

Glen and Audrey proceed to give similar examples from physics. An

example that I (as one of many co-contributors in the wiki-like process

of producing the book) contributed, and they accepted, was:

- The three body problem, now famous after its

central role in Liu Cixin's science-fiction series, shows that an

interaction of even three bodies, even under simple Newtonian physics,

is chaotic enough that its future behavior cannot be predicted with

simple mathematical problems. However, we still regularly solve

trillion-body problems well enough for everyday use by using

seventeenth-century abstractions such as "temperature" and

"pressure".

In biology, a key example is:

- Similarities between organisms and ecosystems: We

have discovered that many diverse organisms ("ecosystems") can exhibit

features similar to multicellular life (homeostasis, fragility to

destruction or over propagation of internal components, etc.)

illustrating emergence and multiscale organization.

The theme of these examples should at this point be easy to see.

There is no single model that can be globally applicable, and the best

that we can do is stitch together many kinds of models that work well in

many kinds of situations. The underlying mechanisms at different scales

are not the same, but they do "rhyme". Social science, they argue, needs

to go in the same direction. And this is exactly where, they argue,

"Technocracy" and "Libertarianism" fail:

In the Technocratic vision we discussed in the previous chapter, the

"messiness" of existing administrative systems is to be replaced by a

massive-scale, unified, rational, scientific, artificially intelligent

planning system. Transcending locality and social diversity, this

unified agent is imagined to give "unbiased" answers to any economic and

social problem, transcending social cleavages and differences. As such,

it seeks to at best paper over and at worst erase, rather than fostering

and harnessing, the social diversity and heterogeneity that ⿻ social

science sees as defining the very objects of interest, engagement, and

value.

In the Libertarian vision, the sovereignty of the atomistic

individual (or in some versions, a homogeneous and tightly aligned group

of individuals) is the central aspiration. Social relations are best

understood in terms of "customers", "exit" and other capitalist

dynamics. Democracy and other means of coping with diversity are viewed

as failure modes for systems that do not achieve sufficient alignment

and freedom.

One particular model that Glen and Audrey come back to again and

again is Georg

Simmel's theory of individuality as arising from each individual

being at a unique intersection of different groups. They describe this

as being a long-lost third alternative to both "atomistic individualism"

and collectivism. They write:

In [Georg Simmel's] view, humans are deeply social creatures and thus

their identities are deeply formed through their social relations.

Humans gain crucial aspects of their sense of self, their goals, and

their meaning through participation in social, linguistic, and

solidaristic groups. In simple societies (e.g., isolated, rural, or

tribal), people spend most of their life interacting with the kin groups

we described above. This circle comes to (primarily) define their

identity collectively, which is why most scholars of simple societies

(for example, anthropologist Marshall Sahlins) tend to favor

methodological collectivism.[14] However, as we noted above, as

societies urbanize social relationships diversify. People work with one

circle, worship with another, support political causes with a third,

recreate with a fourth, cheer for a sports team with a fifth, identify

as discriminated against along with a sixth, and so on.

As this occurs, people come to have, on average, less of their full

sense of self in common with those around them at any time; they begin

to feel "unique" (to put a positive spin on it) and

"isolated/misunderstood" (to put a negative spin on it). This creates a

sense of what he called "qualitaitive individuality" that helps explain

why social scientists focused on complex urban settings (such as

economists) tend to favor methodological individualism. However,

ironically as Simmel points out, such "individuation" occurs precisely

because and to the extent that the "individual" becomes divided among

many loyalties and thus dividual.

This is the core idea that the Plurality book comes back to again and

again: treating connections between individuals as a first

class object in mechanism design, rather than only looking at

individuals themselves.

How does

Plurality differ from libertarianism?

Robert Nozick, in his 1974 book Anarchy,

State and Utopia, argued for a minimal government that performs

basic functions like preventing people from initiating violent force,

but otherwise leaves it up to people to self-organize into communities

that fulfill their values. This book has become something of a manifesto

describing an ideal world for many classical liberals since then.

Two examples that come to mind for me are Robin Hanson's recent post

Libertarianism

as Deep Multiculturalism, and Scott Alexander's 2014 post Archipelago

and Atomic Communitarianism. Robin is interested in this concept

because he wants to see a world that has more of what he calls deep

multiculturalism:

A shallow "multiculturalism" tolerates and even celebrates diverse

cultural markers, such as clothes, food, music, myths, art, furniture,

accents, holidays, and dieties. But it is usually also far less tolerant

of diverse cultural values, such as re war, sex, race, fertility,

marriage, work, children, nature, death, medicine, school, etc. It seeks

a "mutual understanding" that that we are (or should be) all really the

same once we get past our different markers.

In contrast, a deep "multiculturalism" accepts and even celebrates

the co-existence of many cultures with diverse deeply-divergent values.

It seeks ways for a world, and even geographic regions, to encompass

such divergent cultures under substantial peace and prosperity. It

expects some mistrust, conflict, and even hostility between cultures,

due to their divergent values. But it sees this as the price to pay for

deep cultural variety.

As most non-libertarian government activities are mainly justified as

creating and maintaining shared communities/cultures and their values,

this urge to use government to promote shared culture seems the main

obstacle to libertarian-style governance. That is, libertarians hope to

share a government without sharing a community or culture. The usual

"libertarian" vs "statist" political axis might be seen as an axis re

how much we want to share culture, versus allow divergent cultures

Scott Alexander comes to similar conclusions in his 2014 post, though

his underlying goal is slightly different: he wants to find an ideal

political architecture that creates the opportunity for organizations to

support public goods and limit public bads that are culturally

subjective, while limiting the all-too-common tendency for subjective

arguments about higher-order harm ("the gays are corroding the social

fabric") to become a mask for oppression. Balaji's The Network

State is a much more concrete proposal for a social architecture

that tries to accomplish exactly the same objective.

And so a key question worth asking is: where exactly is

libertarianism insufficient to bring about a Plural society? If

I had to summarize the answer in two sentences, I would say:

- Plurality is not just about enabling pluralism,

it's also about harnessing it, and about making a much

more aggressive effort to build higher-level institutions that maximize

positive-sum interactions between different groups and minimize

conflict.

- Plurality is not just at the level of society, it's also

within each individual, allowing each individual to be

part of multiple tribes at the same time.

To understand (2), we can zoom in on one particular example. Let us

look at the debate around Google's on-device anti-fraud scanning system

in the opening section. On one side, we have a tech company releasing a

product that seems to be earnestly motivated by a desire to protect

users from financial scams (which are a very real problem and have cost

people I personally know hundreds of thousands of dollars), which even

goes the extra mile and checks the most important "cypherpunk values"

boxes: the data and computation stays entirely on-device and it's purely

there to warn you, not report you to law enforcement. On the other side,

we see Meredith Whittaker, who sees the offering as a slippery slope

toward something that does do more oppressive things.

Now, let's look at Glen's preferred alternative: a Taiwanese app

called Message Checker.

Message checker is an app that runs on your phone, and intercepts

incoming message notifications and does analysis with them. This

includes features that have nothing to do with scams, such as using

client-side algorithms to identify messages that are most important for

you to look at. But it also detects scams:

A key part of the design is that the app does not force all of its

users into one global set of rules. Instead, it gives users a choice of

which filters they turn on or off:

From top to bottom: URL checking, cryptocurrency address

checking, rumor checking.

These are all filters that are made by the same company. A more ideal

setup would have this be part of the operating system, with an open

marketplace of different filters that you can install, that would be

created by a variety of different commercial and non-profit actors.

The key Pluralist feature of this design is: it gives users

more granular freedom of exit, and avoids being all-or-nothing.

If a norm that on-device anti-fraud scanning must work in this

way can be established, then it seems like it would make Meredith's

dystopia much less likely: if the operator decides to add a filter that

treats information about transgender care (or, if your fears go the

other direction, speech advocating limits on gender self-categorization

in athletics competitions) as dangerous content, then individuals would

be able to simply not install that particular filter, and they would

still benefit from the rest of the anti-scam protection.

One important implication is that "meta-institutions" need to be

designed to encourage other institutions to respect this ideal of

granular freedom of exit - after all, as we've seen with software vendor lock-in,

organizations don't obey this principle automatically!

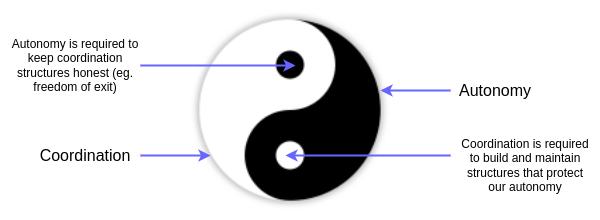

One way to think about the complex interplay between coordination

and autonomy in Plurality.

How does Plurality

differ from democracy?

A lot of the differences between Plural democracy and traditional

democracy become clear once you read the chapter

on voting. Plural voting mechanisms have some strong explicit

answers to the "democracy is two wolves and one sheep voting on what's

for dinner" problem, and related worries about democracy descending into

populism. These solutions build on Glen's

earlier ideas around quadratic voting, but go a step further, by

explicitly counting votes more highly if those votes come from actors

that are more independent of each other. I will get into this more in a

later section.

In addition to this big theoretical leap from only counting

individuals to also counting connections, there are also broad thematic

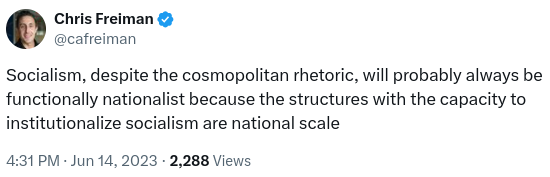

differences. One key difference is Plurality's relationship to nation

states. A major disadvantage of nation-state democracy that speaks to me

personally was summarized well in this tweet by libertarian philosopher

Chris Freiman:

This is a serious gap: two thirds of global inequality is

between countries rather than within countries, an increasing number

of (especially digital) public goods are not global but also not clearly

tied to any specific nation state, and the tools that we use for

communication are highly international. A 21st century program for

democracy should take these basic facts much more seriously.

Plurality is not inherently against the existence of nation states,

but it makes an explicit effort to expand beyond relying on nation

states as its locus of action. It has prescriptions for how all kinds of

actors can act, including transnational organizations, social media

platforms, other types of businesses, artists and more. It also

explicitly acknowledges that for many people, there is no overarching

single nation-state that dominates their lives.

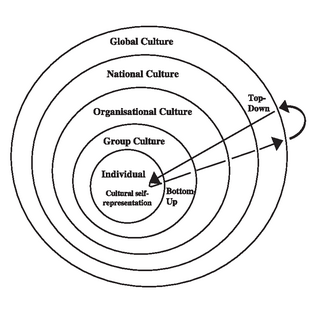

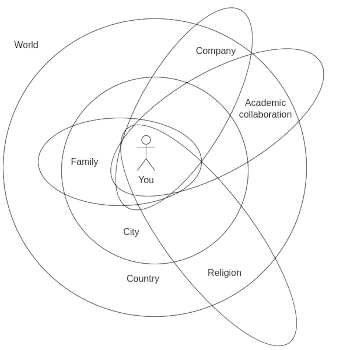

Left: a concentric circle view of society, from a

sociology paper in 2004. Right: a Plural view of society:

intersecting, but non-hierarchical circles.

A big theme of Plurality is expanded on in much more detail in Ken

Suzuki's Smooth

Society and its Enemies: the idea that membership in an organization

should not be treated as a "true-or-false" question. Instead, there

should be different degrees of membership, and these different degrees

would carry different benefits and different levels of obligation. This

is an aspect of society that was always true, but becomes much more

important in an internet-first world where our communities are no longer

necessarily nested and fully overlapping.

What

are some specific technologies that the Plurality vision advocates?

The Plurality book advocates for a pretty wide set of digital and

social technologies that stretch across what are traditionally

considered a large number of "spaces" or industries. I will give

examples by focusing on a few specific categories.

Identity

First, Glen and Audrey's criticism of existing approaches to

identity. Some key quotes from the chapter

on this topic:

Many of the simplest ways to establish identity paradoxically

simultaneously undermine it, especially online. A password is often used

to establish an identity, but unless such authentication is conducted

with great care it can reveal the password more broadly, making it

useless for authentication in the future as attackers will be able to

impersonate them. "Privacy" is often dismissed as "nice to have" and

especially useful for those who "have something to hide". But in

identity systems, the protection of private information is the very core

of utility. Any useful identity system has to be judged on its ability

to simultaneously establish and protect identities.

On biometrics:

[Biometrics] have important limits on their ability to establish and

protect identities. Linking such a wide variety of interactions to a

single identifier associated with a set of biometrics from a single

individual collected at enrollment (or registration) forces a stark

trade-off. On the one hand, if (as in Aadhaar) the administrators of the

program are constantly using biometrics for authentication, they become

able to link or see activities to these done by the person who the

identifier points to, gaining an unprecedented capacity to surveil

citizen activities across a wide range of domains and, potentially, to

undermine or target the identities of vulnerable populations.

On the other hand, if privacy is protected, as in Worldcoin, by using

biometrics only to initialize an account, the system becomes vulnerable

to stealing or selling of accounts, a problem that has decimated the

operation of related services ... If eyeballs can, sometime in the future,

be spoofed by artificial intelligence systems combined with advanced

printing technology, such a system may be subject to an extreme "single

point of failure".

Glen and Audrey's preferred approach is intersectional social

identity: using the entire set of a person's actions and

interactions to serve the underlying goals of identity systems, like

determining the degree of membership in communities and degree of

trustworthiness of a person:

This social, Plural approach to online identity was pioneered by

danah boyd in her astonishingly farsighted master's thesis on "faceted

identity" more than 20 years ago.[28] While she focused primarily on the

benefits of such a system for feelings of personal agency (in the spirit

of Simmel), the potential benefits for the balance between identity

establishment and protection are even more astonishing:

- Comprehensiveness and redundancy: For almost

anything we might want to prove to a stranger, there is some combination

of people and institutions (typically many) who can "vouch" for this

information without any dedicated strategy of surveillance. For example,

a person wanting to prove that they are above a particular age could

call on friends who have known them for a long time, the school they

attended, doctors who verified their age at various times as well, of

course, on governments who verified their age.

- Privacy: Perhaps even more interestingly, all of

these "issuers" of attributes know this information from interactions

that most of us feel consistent with "privacy": we do not get concerned

about the co-knowledge of these social facts in the way we would

surveillance by a corporation or government.

- Security: Plurality also avoids many of the

problems of a "single point of failure". The corruption of even several

individuals and institutions only affects those who rely on them, which

may be a very small part of society, and even for them, the redundancy

described above implies they may only suffer a partial reduction in the

verification they can achieve.

- Recovery: individuals [could] rely on a group of

relationships allowing, for example, 3 of 5 friends or institutions to

recover their key. Such "social recovery" has become the gold standard

in many Web3 communities and is increasingly being adopted even by major

platforms such as Apple.

The core message is any single-factor technique is too

fragile, and so we should use multi-factor techniques. For

account recovery, it is relatively

easy to see how this works, and it's easy to understand the security

model: each user chooses what they trust, and if a particular user makes

a wrong choice, the consequences are largely confined to that user.

Other use cases of identity, however, are more challenging. UBI and

voting, for example, seem like they inherently require global

(or at least community-wide) agreement on who the members of a

community are. But there are efforts that try very hard to bridge this

gap, and create something that comes close to "feeling" like a single

global thing, while being based on subjective multi-factorial trust

under the hood.

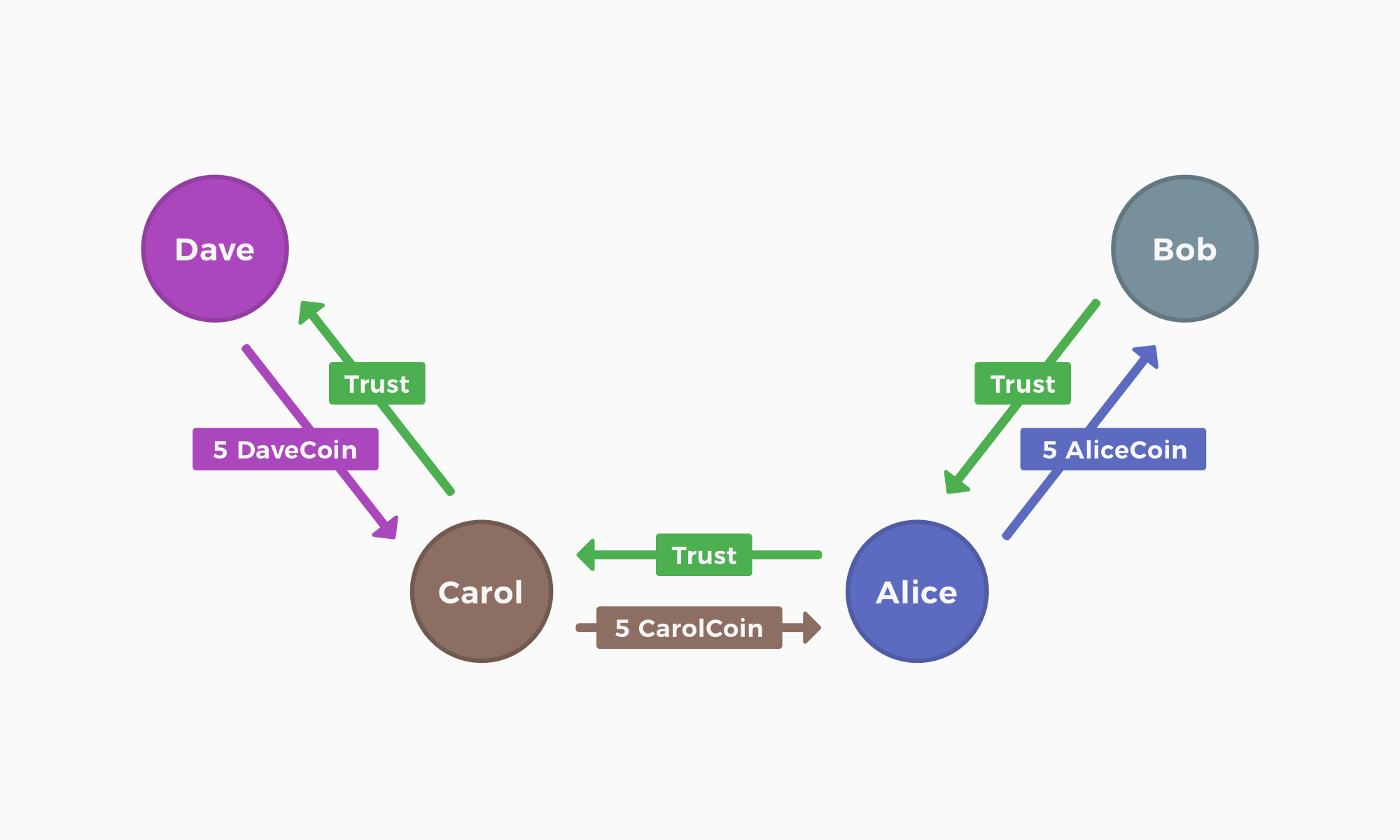

The best example in the Ethereum ecosystem would be Circles, a UBI coin project that is

based on a "web of trust", where anyone can create an account (or an

unlimited number of accounts) that generates 1 CRC per hour, but you

only treat a given account's coins as being "real Circles" if that

account is connected to you through a web-of-trust graph.

Propagation of trust in Circles, from the Circles

whitepaper

Another approach would be to abandon the "you're either a person or

you're not" abstraction entirely, and try to use a combination of

factors to determine the degree of trustworthiness and membership of a

given account, and give it a UBI or voting power proportional to that

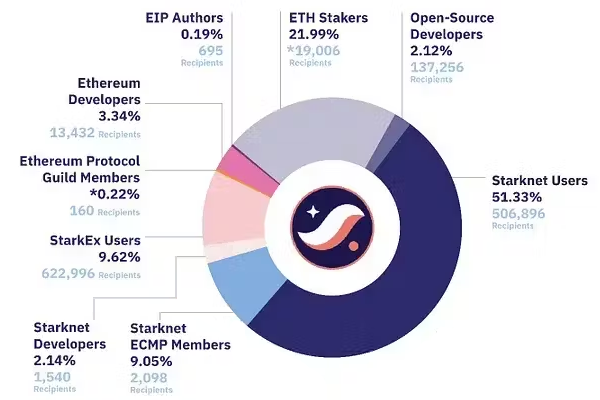

score. Many airdrops that are being done in the Ethereum ecosystem, such

as the Starknet

airdrop, follow these kinds of principles.

Starknet airdrop recipient categories. Many recipients ended up

falling into multiple categories.

Plural Money and Property

In Radical Markets, Glen focused a lot on the virtues "stable and

predictable, but deliberately imperfect" versions of property rights,

like Harberger

taxes. He also focused a lot on "market-like" structures that can

fund public goods and not just private goods, most notably quadratic

voting and quadratic funding. These are both ideas that continue to

be prominent in Plurality. A non-monetary implementation of quadratic

funding called Plural

Credits was used to help record contributions to the book itself.

The ideas around Harberger taxes are somewhat updated, seeking to extend

the idea into mechanisms that allow assets to be partially owned by

multiple different individuals or groups at the same time.

In addition to this ongoing emphasis on very-large-scale market

designs, one new addition to the program is a greater emphasis on

community currencies:

In a polycentric structure, instead of a single universal

currency, a variety of communities would have their own currencies which

could be used in a limited domain. Examples would be vouchers

for housing or schooling, scrip for rides at a fair, or credit at a

university for buying food at various vendors.[18] These currencies

might partially interoperate. For example, two universities in the same

town might allow exchanges between their meal programs. But it would be

against the rules or perhaps even technically impossible for a holder to

sell the community currency for broader currency without community

consent.

The underlying goal is to have a combination of local mechanisms that

are deliberately kept local, and global mechanisms to enable

very-large-scale cooperation. Glen and Audrey see their modified

versions of markets and property as being the best candidates for

very-large-scale global cooperation:

Those pursuing Plurality should not wish markets away. Something must

coordinate at least coexistence if not collaboration across the broadest

social distances and many other ways to achieve this, even ones as thin

as voting, carry much greater risks of homogenization precisely because

they involve deeper ties. Socially aware global markets offer much

greater prospect for Plurality than a global government. Markets must

evolve and thrive, along with so many other modes of collaboration, to

secure a Plural future.

Voting

In Radical Markets, Glen advocated quadratic voting, which deals with

the problem of allowing voters to express different strength of

preferences but while avoiding failure modes where the most extreme

or well-resourced voice dominates decision-making. In Plurality, the

core problem that Glen and Audrey are trying to solve is different, and

this

section does a good job of summarizing what new problem they are

trying to solve:

it is natural, but misleading, to give a party with twice the

legitimate stake in a decision twice the votes. The reason is that this

will typically give them more than twice as much power. Uncoordinated

voters on average cancel one another out and thus the total influence of

10,000 completely independent voters is much smaller than the influence

of one person with 10,000 votes.

When background signals are completely uncorrelated and there are

many of them, there is a simple way to mathematically account for this:

a series of uncorrelated signals grows as the square root of their

number, while a correlated signal grows in linear proportion to its

strength. Thus 10,000 uncorrelated votes will weigh as heavily as only

100 correlated ones.

To fix this, Glen and Audrey argue for designing voting mechanisms

with a principle of "degressive proportionality": treat uncorrelated

signals additively, but give N correlated signals only sqrt(N)

votes.

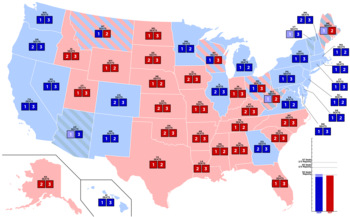

A precedent for this kind of approach exists in countries like the

United States and in international bodies, where there are typically

some chambers of governance that give sub-units (states in the former

case, countries in the latter case) a quantity of voting power

proportional to their population or economic power, and other chambers

of governance that give one unit of voting power to each sub-unit

regardless of size. The theory is that ten million voters from a big

state matter more than a million voters from a small state, but they

represent a more correlated signal than ten million voters from ten

different states, and so the voting power that the ten million voters

from a big state should be somewhere in between those two extremes.

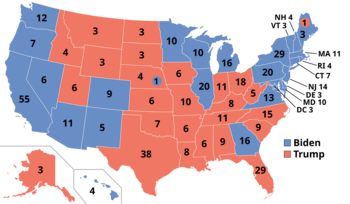

Left: US senate, two senators per state regardless of size.

Right: US electoral college, senator count roughly proportional to

population.

The key challenge to making this kind of design work in a more

general way is, of course, in determining who is "uncorrelated".

Coordinated actors pretending to be uncoordinated to increase their

legitimacy (aka "astroturfing", "decentralization larping", "puppet

states"...) is already a mainstream political tactic and has been for

centuries. If we instantiate a mechanism that determines who is

correlated to whom by analyzing Twitter posts, people will start

crafting their Twitter content to appear as uncorrelated as possible

toward the algorithm, and perhaps even intentionally create and use bots

to do this.

Here, I can plug my own proposed solution to this problem: vote

simultaneously on multiple issues, and use the votes themselves as a

signal of who is correlated to whom. One implementation of this was in

pairwise

quadratic funding, which allocates to each pair of

participants a fixed budget, which is then split based on the

intersection of how that pair votes. You can do a similar thing for

voting: instead of giving one vote to each voter, you can give one

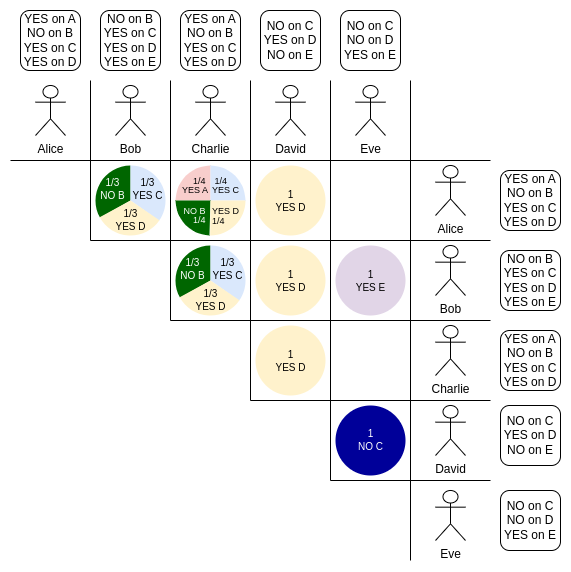

(splittable) vote to each pair of voters:

If you count by raw numbers, YES wins 3-2 on issue C. But Alice,

Bob and Charlie are highly correlated voters: they agree on almost

everything. Meanwhile, David and Eve agree on nothing but C. In pairwise

voting, the whole "NO on C" vote of the (David, Eve) pair would be

allocated to C, and it would be enough to overpower the "YES on C" votes

of Alice, Bob and Charlie, whose pairwise votes for C add up to only

11/12.

The key trick in this kind of design is that the determination of who

is "correlated" and "uncorrelated" is intrinsic to the mechanism. The

more that two participants agree on one issue, the less their vote

counts on all other issues. A set of 100 "organic" diverse participants

would get a pretty high weight on their votes, because the overlap area

of any two participants is relatively small. Meanwhile, a set of 100

people who all have similar beliefs and listen to the same media would

get a lower weight, because their overlap area is higher. And a set of

100 accounts that are all being controlled by the same owner would have

perfect overlap, because that's the strategy that maximizes the owner's

objectives, but they would get the lowest weight of all.

This "pairwise" approach is not the mathematically ideal way to

implement this kind of thing: in the case of quadratic funding, the

amount of money that an attacker can extract grows with the

square of the number of accounts they control, whereas ideally

it would be linear. There is an open research problem in

specifying an "ideal" mechanism, whether for quadratic funding or

voting, that has the strongest properties when faced with attackers

controlling multiple accounts or correlated voters.

This is a new type of democracy that naturally corrects for the

phenomenon that internet discourse sometimes labels as "NPCs": a large mass

of people that might as well just be one person because they're all

consuming exactly the same sources of information and believe all of the

same things.

Conversations

As I've said on many occasions especially in the context of DAOs, the

success or failure of governance depends ~20% on the formal governance

mechanism, and ~80% on the structure of communication that the

participants engage in before they get to the step where they've settled

on their opinions and are inputting them into the governance. To that

end, Glen and Audrey have also spent quite a lot of time thinking about

better technologies for large-scale conversations.

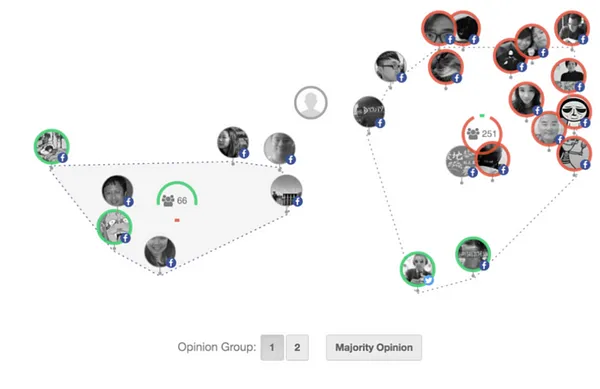

One conversation tool that they focus on a lot is Polis. Polis is a system that allows

people to submit statements about an issue, and vote on each other's

statements. At the end of a round, it identifies the different major

"clusters" in the different points of view, and surfaces the statements

that were the most effective at getting support from all clusters.

Source: https://words.democracy.earth/hacking-ideology-pol-is-and-vtaiwan-570d36442ee5

Polis was actually used in Taiwan during some public deliberations

over proposed laws, including agreeing on the rules for Uber-like ride

hailing services. It has been used in several other contexts around the

world as well, including some experiments within the Ethereum

community.

The second tool that they focus on is one that has had much more

success becoming mainstream, though in large part due to its "unfair

advantage" from being introduced into a pre-existing social media

platform with hundreds of millions of users: Twitter's Community

Notes.

Community Notes similarly uses an algorithm that allows anyone to

submit a proposed note for a post, and shows the notes that are rated

the most highly by people who disagree on most other notes. I described

this algorithm in much more detail in my

review of the platform. Since then, Youtube has

announced that they are planning to introduce a similar feature.

Glen and Audrey want to see the underlying ideas behind these

mechanisms expanded on, and used much more broadly throughout the

platforms:

While [Community Notes] currently lines up all opinions across the

platform on a single spectrum, one can imagine mapping out a range of

communities within the platform and harnessing its bridging-based

approach not just to prioritize notes, but to prioritize content for

attention in the first place.

The end goal is to try to create large-scale discussion platforms

that are not designed to maximize metrics like "engagement", but are

instead intentionally optimized around surfacing points of consensus

between different groups. Live and let live, but also identify and take

advantage of every possible opportunity to cooperate.

Brain-to-brain

communication and virtual reality

Glen and Audrey spend two whole chapters on "post-symbolic

communication" and "immersive

shared reality". Here, the goal is to spread information from person

to person in a way that is much higher bandwidth than what can be

accomplished with markets or conversation.

Glen and Audrey describe an exhibit in Tokyo that gives the user a

realistic sensory experience of what it's like to be old:

Visors blur vision, mimicking cataracts. Sounds are stripped of high

pitches. In a photo booth that mirrors the trials of aged perception,

facial expressions are faded and blurred. The simple act of recalling a

shopping list committed to memory becomes an odyssey as one is

ceaselessly interrupted in a bustling market. Walking in place on pedals

with ankle weights on and while leaning on a cart simulates the wear of

time on the body or the weight of age on posture.

They argue that even more valuable and high-fidelity versions of

these kinds of experiences can be made with future technologies like

brain-computer interfaces. "Immersive shared reality", a cluster

encompassing what we often call "virtual reality" or "the metaverse" but

going broader than that, is described as a design space halfway in

between post-symbolic communication and conversations.

Another recent book that I have read on similar topics is Herman

Narula's Virtual

Society: The Metaverse and the New Frontiers of Human

Experience. Herman focuses heavily on the social value

of virtual worlds, and the ways in which virtual worlds can support

coordination within societies if they are imbued with the right social

meaning. He also focuses on the risks of centralized control, arguing

that an ideal metaverse would be created by something more like a

non-profit DAO than a traditional corporation. Glen and Audrey have very

similar concerns:

Corporate control, surveillance, and monopolization: ISR blurs the

lines between public and private, where digital spaces can be

simultaneously intimate and open to wide audiences or observed by

corporate service providers. Unless ISR networks are built according to

the principles of rights and interoperability we emphasized above and

governed by the broader Plurality governance approaches that much of the

rest of this part of the book are devoted to, they will become the most

iron monopolistic cages we have known.

If I had to point to one difference in their visions, it is this.

Virtual Society focuses much more heavily on the

shared-storytelling and long-term continuity aspects of virtual worlds,

pointing out how games like Minecraft win the hearts and minds of

hundreds of millions despite being, by modern standards, very limited

from a cinematic immersion perspective. Plurality, on the other

hand, seems to focus somewhat more (though far from exclusively) on

sensory immersion, and is more okay with short-duration experiences. The

argument is that sensory immersion is uniquely powerful in its ability

to convey certain kinds of information that we would otherwise have a

hard time getting. Time will tell which of these visions, or what kind

of combination of both, will prove successful.

Where

does Plurality stand in the modern ideological landscape?

When I reflect on the political shifts that we've seen since the

early 2010s, one thing that strikes me is that the movements that

succeed in the current climate all seem to have one thing in common:

they are all object-level

rather than meta-level. That is, rather than seeking to promote

broad overarching principles for how social or political questions

should be decided, they seek to promote specific stances on specific

issues. A few examples that come to mind include:

- YIMBY: standing for "yes, in my back yard", the

YIMBY movement seeks to fight highly restrictive zoning regulations (eg.

in

the San Francisco Bay Area), and expand freedom to build housing. If

successful, they argue that this would knock down the single largest

component of many people's cost of living, and increase

GDP by up to 36%. YIMBY has recently had a large number of political

wins, including a major zoning

liberalization bill in California.

- The crypto space: ideologically, the space stands

for freedom, decentralization, openness and anti-censorship as

principles. In practice, large parts of it end up focusing more

specifically on openness of a global financial system and freedom to

hold and spend money.

- Life extension: the concept of using biomedical

research to figure out how to intervene in the aging process

before it progresses to the point of being a disease, and in

doing so potentially give us a far longer (and entirely healthy)

lifespan, has become much more mainstream over the last ten years.

- Effective altruism: historically, the effective altruism movement

has stood for the broad application of a formula: (i) caring about doing

the most good, and (ii) being rigorous about determining which charities

actually accomplish that goal, noting that some

charities are thousands of times more effective than others.

More recently, however, the most prominent parts of the movement have

made a shift toward focusing on the single issue of AI

safety.

Of the modern movements that have not become issue-driven in

this way, a large portion could be viewed as obfuscated personality

cults, rallying around whatever set of positions is adopted and changed

in real time by a single leader or small well-coordinated elite. And

still others can be criticized for being ineffective and inconsistent,

constantly trying to force an ever-changing list of causes under the

umbrella of an ill-defined and unprincipled "Omnicause".

If I had to ask myself why these shifts are taking place, I

would say something like this: large groups have to coordinate

around something. And realistically, you either (i) coordinate

around principles, (ii) coordinate around a task, or (iii) coordinate

around a leader. When the pre-existing set of principles

becomes perceived as being worn out and less effective, the other two

alternatives naturally become more popular.

Coordinating around a task is powerful, but it is temporary, and any

social capital you build up easily dissipates once that particular task

is complete. Leaders and principles are powerful because they are

factories of tasks: they can keep outputting new things to do

and new answers for how to resolve new problems again and again. And of

those two options, principles are far more socially scalable and far

more durable.

Plurality seems to stand sharply in opposition to the broader trends.

Together with very few other modern movements (perhaps network states),

it goes far beyond any single task in scope, and it seeks to coordinate

around a principle, and not a leader. One way to understand

Plurality, is that it recognizes that (at least at very large scales)

coordinating around principles is the superior point on the triangle,

and it's trying to do the hard work of figuring out the new set of

principles that work well for the 21st century. Radical Markets

was trying to reinvent the fields of economics and mechanism design.

Plurality is trying to reinvent liberalism.

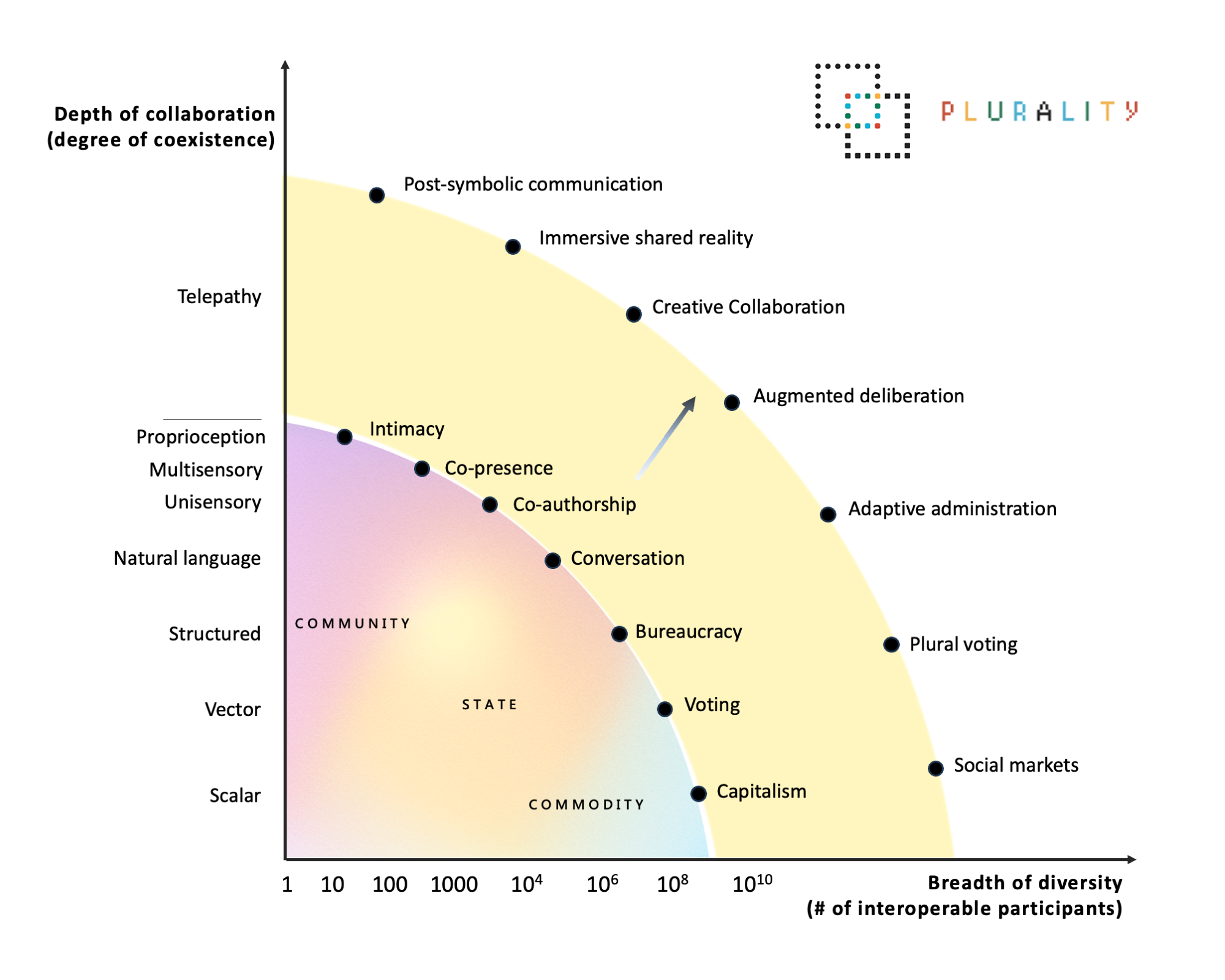

The way in which all of the mechanisms described in the sections

above combine into a single framework is best exemplified in this chart

by Gisele Chou:

On one level, the framework makes total sense. The philosopher Nassim

Taleb loves

to quote Geoff and Vince Graham to describe his rejection of

"scale-free universalism": "I am, at the Fed level, libertarian; at the

state level, Republican; at the local level, Democrat; and at the family

and friends level, a socialist". Plurality philosophy takes this

seriously, recommending different mechanisms at different scales.

On another level, it sometimes feels like "the Plurality vibe" is

acting as an umbrella that is combining very different

concepts, that have very different reasons for accepting or

rejecting them. For example, "creating healthy connections between

people is very important" is a very different statement from "voting

mechanisms need to take differences in degree of connectedness into

account". It's entirely possible that pairwise quadratic funding can be

used to make a new and better United Nations that subsidizes cooperation

and world peace, but at the same time "creative collaborations" are

overrated and great works should be the vision of one author. Some of

this seeming inconsistency comes from the book's diverse collaborative

authorship: for example, the virtual reality and brain-to-brain

sections, and much of the work on correlation discounts, was written by

Puja Ohlhaver, and her focuses are not quite the same as Glen's or

Audrey's. But this is a property of all philosophies: 19th century

liberalism combined democracy and markets, but it was a composite work

of many people with different beliefs. Even today, there are many people

who like democracy and are suspicious of markets, or like markets and

are suspicious of democracy.

And so one question worth asking is: if your background

instincts on various questions differ from "the Plurality vibe" on some

dimensions, can you still benefit from Plurality ideas? I will

argue that the answer is yes.

Is

Plurality compatible with wanting a crazy exponential future?

One of the impressions that you might get from reading Plurality is

that, while Glen and Audrey's meta-level visions for conversations and

governance are fascinating, they don't really see a future where

anything too technologically radical happens. Here

is a list of specific object-level outcomes that they hope to

achieve:

- The workplace, where we believe it could raise economic

output by 10% and increase the growth rate by a percentage

point

- Health, where we believe it can extend human life by two

decades

- Media, where it can heal the divides opened by social media, provide

sustainable funding, expand participation and dramatically increase

press freedom

- Environment, where it is core to addressing most of the

serious environmental problems we face, perhaps even more so

than traditional "green" technologies

- Learning, where it can upend the linear structure of current

schooling to allow far more diverse and flexible, lifelong

learning paths.

These are very good outcomes, and they are ambitious goals for the

next ten years. But the goals that I want to see out of a

technologically advanced society are much greater and deeper than this.

Reading this section reminded me of the recent review

I made of the museums of the future in Dubai vs Tokyo:

But their proposed solutions are mostly tweaks that try to make the

world more gentle and friendly to people suffering from these

conditions: robots that can help guide people, writing on business cards

in Braille, and the like. These are really valuable things that can

improve the lives of many people. But they are not what I would expect

to see in a museum of the future in 2024: a solution that lets people

actually see and hear again, such as optic nerve regeneration and brain

computer interfaces.

Something about the Dubai approach to these questions speaks deeply

to my soul, in a way that the Tokyo approach does not. I do not

want a future that is 1.2x better than the present, where I can enjoy 84

years of comfort instead of 70 years of comfort. I want a future that is

10000x better than the present ... If I become infirm and weak

for a medical reason, it would certainly be an improvement to live in an

environment designed to still let me feel comfortable despite these

disadvantages. But what I really want is for technology to fix

me so that I can once again become strong.

Dubai is an interesting example because it also uses another

technology that speaks deeply to my soul: geoengineering. Today, the

usage, and risks, of geoengineering are on a fairly local scale: the

UAE engages in cloud seeding and some blamed Dubai's recent floods

on it, though the

expert consensus seems to disagree. Tomorrow, however, there may be

much bigger prizes. One example is solar

geoengineering: instead of re-organizing our entire economy and

society to keep CO2 levels reasonably low and the planet reasonably

cool, there is a chance that all it takes to achieve a 1-4⁰C temperature

reduction is sprinkling the right salts into the air. Today, these ideas

are highly speculative, and the science is far too early to commit to

them, or use them as an excuse not to do other things. Even more modest

proposals like artificial lakes cause

problems with parasites. But as this century progresses, our ability

to understand the consequences of doing things like this will improve.

Much like medicine went from being often

net-harmful in earlier periods to crucially lifesaving today, our

ability to heal the planet may well go through a similar transition. But

even after the scientific issues become much more

well-understood, another really big question looms: how the hell

do we govern such a thing?

Environmental geopolitics is already a big question today. There are

already disputes

over water rights from rivers. If transformative continent-scale or

world-scale geoengineering becomes viable, these issues will become much

more high-stakes. Today, it seems hard to imagine any solution other a

few powerful countries coming together to decide everything on

humanity's behalf. But Plurality ideas may well be the best shot

we have at coming up with something better. Ideas around common

property, where certain resources or features of the environment can

have shared ownership between multiple countries, or even non-country

entities tasked with protecting the interests of the natural environment

or of the future, seem compelling in principle. Historically, the

challenge has been that such ideas are hard to formalize. Plurality

offers a bunch of theoretical tools to do just that.

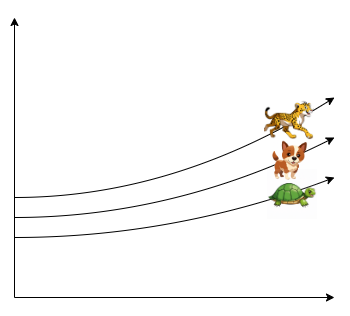

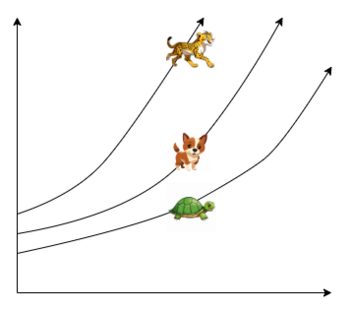

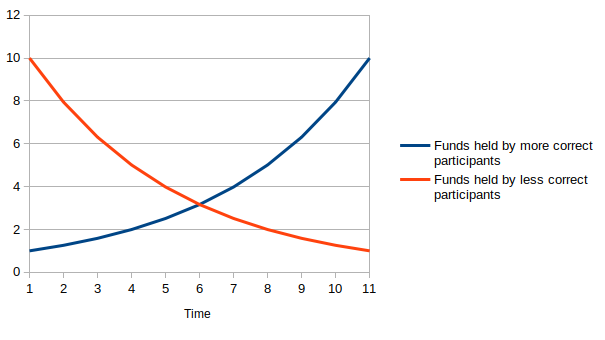

If we zoom back out beyond the geoengineering issue, and think about

the category of "crazy exponential technology" in general, it

might feel like there is a tension between pluralism and technology

leading to exponential growth in capabilities. If different

entities in society progress according to a linear, or slightly

superlinear, trajectory, then small differences at time T remain small

differences at time T+1, and so the system is stable. But if the

progress is super-exponential, then small differences turn into

larger and larger differences, even in proportional terms, and the

natural outcome is one entity overtaking everything else.

Left: slightly super-linear growth. Small differences at the

start become small differences at the end. Right: super-exponential

growth. Small differences at the start become very large differences

quickly.

Historically this has actually been a tradeoff. If you were to ask

which 1700s-era institutions feel the most "pluralist", you might have

said things like deeply-rooted extended family ties and trade guilds.

However, the Industrial Revolution sweeping these institutions away and

replacing them with economies of scale and industrial capitalism is

often precisely the thing that is credited

with enabling great economic growth.

However, I would argue that the static pluralism of the

pre-industrial age and Glen and Audrey's Plurality are fundamentally

different. Pre-industrial static pluralism was crushed by what

Glen calls "increasing returns". Plurality has tools specifically

designed for handling it: democratic mechanisms for funding public

goods, such as quadratic funding, and more limited versions of property

rights, where (especially) if you build something really powerful, you

only have partial ownership of what you build. With these techniques, we

can prevent super-exponential growth at the scale of human

civilization from turning into super-exponential growth in

disparities of resources and power. Instead, we design property

rights in such a way that a rising tide is forced to lift all boats.

Hence, I would argue that exponential growth in technological

capability and Plurality governance ideas are highly

complementary.

Is

Plurality compatible with valuing excellence and expertise?

There is a strand in political thought that can be summarized as

"elitist liberalism": valuing the benefits of free choice and democracy

but acknowledging that some people's inputs are much higher quality than

others, and wanting to put friction or limits on democracy to give

elites more room to maneuver. Some recent examples include:

- Richard Hanania's concept

of "Nietzschean liberalism" where he seeks to reconcile his

long-held belief that "some humans are in a very deep sense better than

other humans ... society disproportionately benefits from the scientific

and artistic genius of a select few", and his growing appreciation for

the benefits of liberal democracy in avoiding outcomes that are

really terrible and in not over-entrenching specific elites

that have bad ideas.

- Garrett Jones's 10%

Less Democracy, which advocates for more indirect

democracy through longer term durations, more appointed positions, and

similar mechanisms.

- Bryan Caplan's guarded

support for free speech as an institution that at least

gives a chance for counter-elites to form and develop ideas under

hostile conditions, even if an open "marketplace of ideas" is far from a

sufficient guarantee that good ideas will win broader public

opinion.

There are parallel arguments on the other side of the political

spectrum, though the language there tends to focus on "professional

expertise" rather than "excellence" or "intelligence". The types of

solutions that people who make these arguments advocate often involve

making compromises between democracy and either plutocracy or

technocracy (or something that risks being worse than both) as ways of

trying to select for excellence. But what if, instead of making this

kind of compromise, we try harder to solve the problem directly?

If we start from a goal that we want an open pluralistic

mechanism that allows different people and groups to express and execute

on their diverse ideas so that the best can win, we can ask the

question: how would we optimize institutions with that idea in

mind?

One possible answer is prediction

markets.

Left: Elon Musk proclaiming that civil war in the UK "is

inevitable". Right: Polymarket bettors, with actual skin in the game,

think that the probability of a civil war is.... 3% (and I think even

that's way too high, and I made a bet to that effect)

Prediction markets are an institution that allows different people to

express their opinions on what will happen in the future. The virtues of

prediction markets come from the idea that people are more likely to

give high-quality opinions when they have "skin in the game", and that

the quality of the system improves over time because people with

incorrect opinions will lose money, and people with correct opinions

will gain money.

It is important to point out that while prediction markets

are pluralistic in the sense of being open to diverse participants, they

are not Pluralistic in Glen and Audrey's sense of the word.

This is because they are a purely financial mechanism: they do not

distinguish between $1 million bet by one person and $1 million bet by a

million unconnected people. One way to make prediction markets more

Pluralistic would be to introduce per-person subsidies, and

prevent people from outsourcing the bets that they make with these

subsidies. There are some mathematical arguments why this could do an

even better job than traditional prediction markets of eliciting

participants' knowledge and insights. Another option is to run a

prediction market and in parallel run a Polis-style discussion platform

that encourages people to submit their reasoning for why they believe

certain things - perhaps using soulbound

proofs of previous track record on the markets to determine whose voice

carries more weight.

Prediction markets are a tool that can be applied in many form

factors and contexts. One example is retroactive

public goods funding, where public goods are funded after

they have made an impact and enough time has passed that the impact can

be evaluated. RPGF is typically conceived of as being paired with an

investment ecosystem, where ahead-of-time funding for public

goods projects would be provided by venture capital funds and investors

making predictions about which projects will succeed in the future. Both

the after-the-fact piece (evaluation) and the before-the-fact piece

(prediction) can be made more Pluralistic: some form of quadratic voting

for the former, and per-person subsidies for the latter.

The Plurality book and related writings do not really feature a

notion of "better vs worse" ideas and perspectives, only of getting more

benefit from aggregating more diverse perspectives. On the

level of "vibes", I think there is an actual tension here. However, if

you believe that the "better vs worse" axis is important, then I do not

think that these focuses are inherently incompatible: there are ways to

take the ideas of one to improve mechanisms that are designed for the

other.

Where could these

ideas be applied first?

The most natural place to apply Plurality ideas is social settings

that are already facing the problem of how to improve collaboration

between diverse and interacting tribes while avoiding centralization and

protecting participants' autonomy. I personally am most bullish on

experimentation in three places: social media,

blockchain ecosystems and local

government. Particular examples include:

- Twitter's Community

Notes, whose note ranking system is already designed to

favor notes that gain support across a wide spectrum of participants.

One natural path toward improving Community Notes would be to find ways

to combine it with prediction markets, thereby encouraging sophisticated

actors to much more quickly flag posts that will get noted.

- User-facing anti-fraud software. Message Checker,

as well as the Brave browser and some

crypto wallets, are early examples of a paradigm of software that works

aggressively on the user's behalf to protect the user from threats

without needing centralized backdoors. I expect that Software like this

will be very important, but it carries the inherent political question

of determining what is and is not a threat. Plurality ideas can be of

help in navigating this issue.

- Public goods funding in blockchain ecosystems. The

Ethereum ecosystem makes heavy use

of quadratic funding and retroactive funding

already. Pluralistic mechanisms could help in bounding the vulnerability

of these mechanisms to collusion, and subsidize collaboration between

parts of the ecosystem that face pressures to act competitively towards

each other, eg. layer-2 scaling platforms and wallets.

- Network

states, popup

cities and related concepts. New voluntary communities that

form online based on shared interests, and then "materialize" offline,

have many needs for (i) having less dictatorial forms of governance

internally, (ii) cooperating more between each other, and (iii)

cooperating more with the physical jurisdictions in which they are

based. Plurality mechanisms could improve on all three.

- Publicly funded news media. Historically, media has

been funded either by listeners, or by the administrative arm of a

centralized state. Plurality mechanisms could enable more democratic

mechanisms, which also explicitly try to bridge across and reduce rather

than increase polarization.

- Local public goods: there are many hyper-local

governance and resource allocation decisions that could benefit from

Plurality mechanisms; my post on crypto

cities contains some examples. One possible place to start is

quasi-cities with highly sophisticated residents, such as